Life’s full of choices. Some decisions are relatively easy to make: “What do I want to eat for dinner?” is low-risk and comparatively inconsequential in the grand scheme of things. Other scenarios, however, are much, much more difficult. Quitting a job, starting a family, texting that problematic ex–these all potentially result in major life ramifications. But what choices do people struggle with the most?

To get a better sense of our daily dilemmas, psychologists at the University of Zurich in Switzerland crafted an open-ended survey to assess commonly shared stress surrounding various uncertainties. Instead of tasking over 4,380 volunteers in Switzerland to choose from a closed set of risky scenarios, the researchers led by Renato Frey left the answer field entirely blank. Based on the results detailed in their study published in the journal Psychological Science, there are some consistencies to what’s troubling us the most in 2025.

“In a relatively straightforward way, we just asked our study participants to report a single risky choice,” Frey said in a statement. “By and large, the distributions of these risky choices to different life domains stay fairly constant.

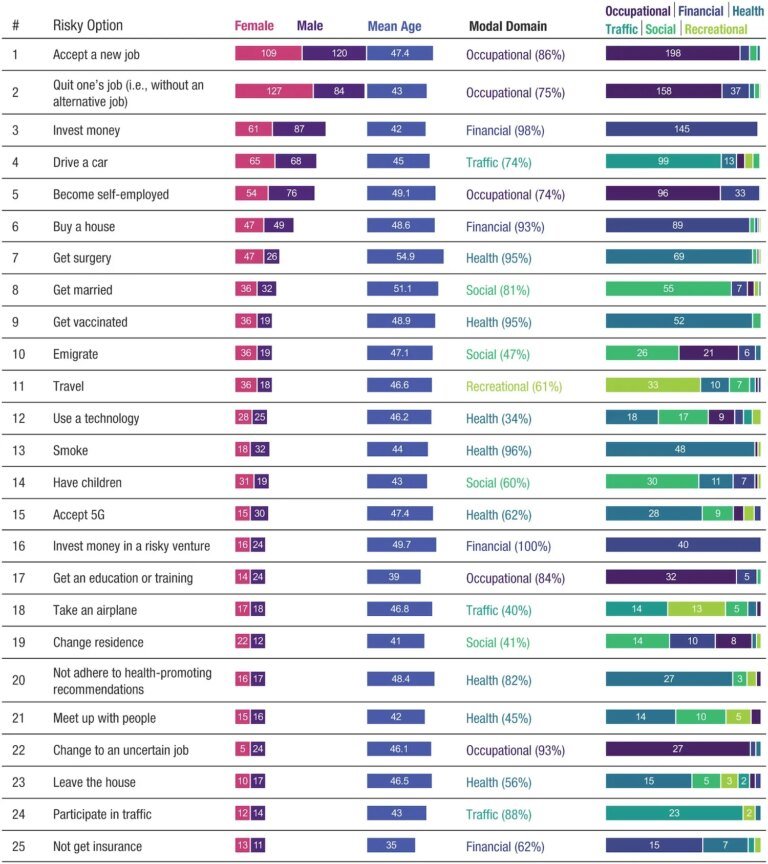

No matter the demographic, the majority of people most frequently associate risk with accepting a new job. This was immediately followed by quitting a job, as well as investing money, driving, becoming self-employed, and buying a house.

Surprisingly, the results were often contrary to what many of the study’s authors assumed before conducting the survey. Where researchers assumed health or daily activities like traveling alone might top the list, it turned out to be the opposite.

“That was quite an interesting find, but according to our data, it seems to be a bit like vice-versa,” said Frey. “First and foremost, people think of occupational risky choices.”

Frey’s team ultimately compiled a condensed list of 100 of the most common risky decisions experienced by everyday people. These are further broken down based on subject matter such as “career,” “financial,” or “relationships,” as well as demographics like age and gender identification. This allows reviewers to focus on different aspects and chart overarching themes. One potential example offered by the study’s authors concerned the timing of their survey. The researchers examined if risky choices shifted before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead of any marked changes, Frey noted the answers remained “surprisingly stable.”

The only thing that differed between certain participants was the manner in which the question was posed. “Risky” was left intentionally vague to obtain the broadest types of answers possible. For certain people, risk is mostly associated with randomness like gambling, but others may think of highly consequential situations. Volunteers were also asked to explain a risky choice they decided themselves, while others recounted a story from somebody in their social circle. They were then asked to describe the outcome for both these riskier and safer decisions.

However, demographics did influence certain responses. Younger adults usually listed quitting a job as a big risk, while older respondents stressed over accepting a new job.

“These more nuanced patterns help us understand essentially which subgroups of the population are exposed to which risky choices,” Frey explained.

The study’s authors believe the new database could soon help policymakers determine which populations require additional decision aids or support, while other psychologists can use the information to understand larger themes between patients.

“I think this [study] could serve as kind of a blueprint for how, at least every once in a while, we should probably reach out and do this more discovery-oriented, data-driven, bottom-up research,” said Frey.