When asked to evaluate how good we are at something, we tend to get that estimation completely wrong. It’s a universal human tendency, with the effect seen most strongly in those with lower levels of ability. Called the Dunning-Kruger effect, after the psychologists who first studied it, this phenomenon means people who aren’t very good at a given task are overconfident, while people with high ability tend to underestimate their skills. It’s often revealed by cognitive tests — which contain problems to assess attention, decision-making, judgment and language.

But now, scientists at Finland’s Aalto University (together with collaborators in Germany and Canada) have found that using artificial intelligence (AI) all but removes the Dunning-Kruger effect — in fact, it almost reverses it.

As we all become more AI-literate thanks to the proliferation of large language models (LLMs), the researchers expected participants to be not only better at interacting with AI systems but also better at judging their performance in using them. “Instead, our findings reveal a significant inability to assess one’s performance accurately when using AI equally across our sample,” Robin Welsch, an Aalto University computer scientist who co-authored the report, said in a statement.

Flattening the curve

In the study, scientists gave 500 subjects logical reasoning tasks from the Law School Admission Test, with half allowed to use the popular AI chatbot ChatGPT. Both groups were later quizzed on both their AI literacy and how well they thought they performed, and promised extra compensation if they assessed their own performance accurately.

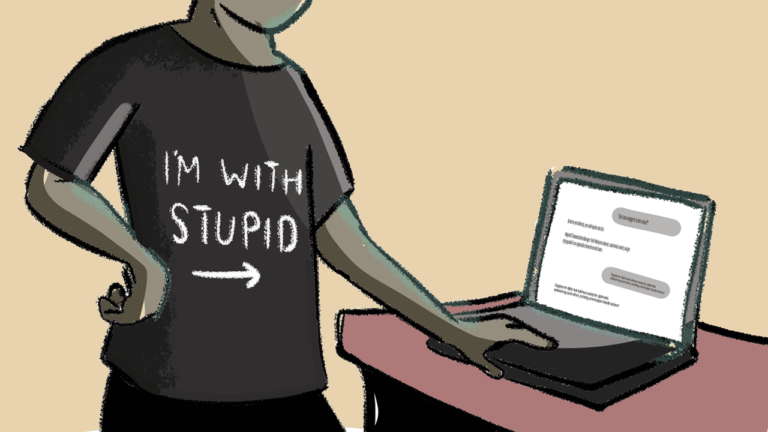

The reasons behind the findings are varied. Because AI users were usually satisfied with their answer after only one question or prompt, accepting the answer without further checking or confirmation, they can be said to have engaged in what Welsch calls “cognitive offloading” — interrogating the question with reduced reflection, and approaching it in a more “shallow” way.

Less engagement in our own reasoning — termed “metacognitive monitoring” — means we bypass the usual feedback loops of critical thinking, which reduces our ability to gauge our performance accurately.

Even more revealing was the fact that we all overestimate our abilities when using AI, regardless of our intelligence, with the gap between high and low-skill users shrinking. The study attributed this to the fact that LLMs help everyone perform better to some degree.

Although the researchers didn’t refer to this directly, the finding also comes at a time when scientists are questioning we’re starting to ask whether common LLMs are too sycophantic. The Aalto team warned of several potential ramifications as AI becomes more widespread.

Firstly, metacognitive accuracy overall might suffer. As we rely more on results without rigorously questioning them, a trade-off emerges whereby user performance improves but an appreciation of how well we do with tasks declines. Without reflecting on results, error checking or deeper reasoning, we risk dumbing down our ability to source information reliably, the scientists said in the study.

What’s more, the flattening of the Dunning-Kruger Effect will mean we’ll all continue to overestimate our abilities while using AI, with the more AI-literate among us doing so even more — leading to an increased climate of miscalculated decision-making and an erosion of skills.

One of the methods the study suggests to arrest such decline is to have AI itself encourage further questioning in users, with developers reorienting responses to encourage reflection — literally asking questions like “how confident are you in this answer?” or “what might you have missed?” or otherwise promoting further interaction through measures like confidence scores.

The new research adds further weight to the growing belief that, as the Royal Society recently argued, AI training should include critical thinking, not just technical ability. “We… offer design recommendations for interactive AI systems to enhance metacognitive monitoring by empowering users to critically reflect on their performance,” the scientists said.