For more than 4,000 years, Indigenous Americans painted rock art depicting their conception of the universe in what is now southwestern Texas and northern Mexico, a new study finds.

Innovative dating techniques revealed that the rock art, known as the Pecos River style tradition, likely first appeared almost 6,000 years ago and persisted until about 1,400 to 1,000 years ago, spanning roughly 175 generations.

“Frankly, we were stunned to discover that the murals remained in production for over 4,000 years and that the rule-bound painting sequence persisted throughout that period as well,” study co-author Carolyn Boyd, a professor of anthropology at Texas State University, told Live Science in an email.

She compared the canyonlands to an “ancient library containing hundreds of books authored by 175 generations of painters,” adding that “the stories they tell are still being told today.”

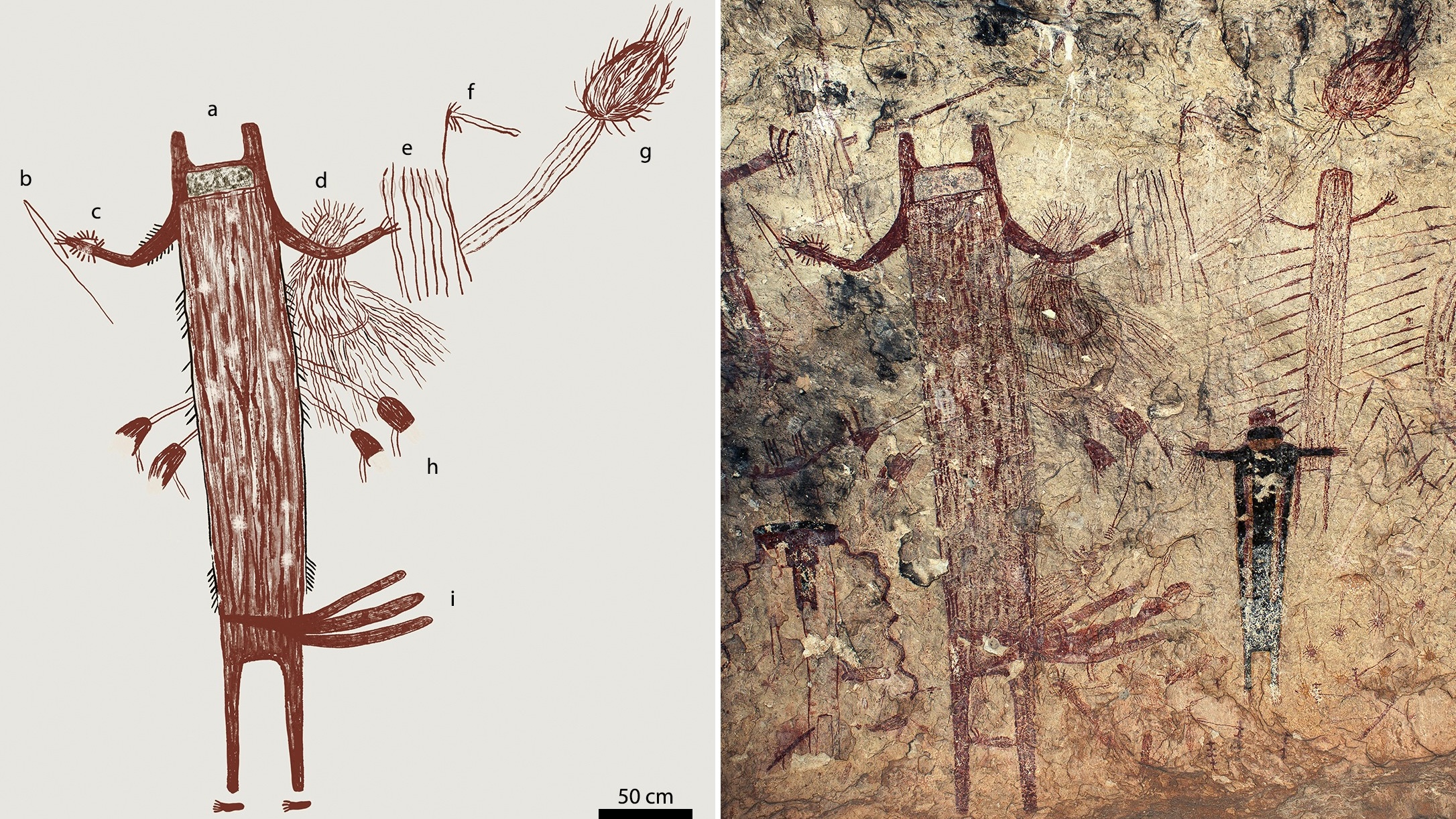

The ancient murals found on limestone rock faces across the canyonlands consist of elaborate multicolored paintings depicting animal- and human-like figures, as well as more enigmatic symbols. The artists who made them created visual narratives that relate myths and prescribe rituals, according to Boyd.

“Many of the 200-plus murals in the region are huge; some span over 100 feet [30 meters] long and 20 feet [6 m] tall and contain hundreds of skillfully painted images,” Boyd said.

The painters were nomadic hunter-gatherers, but their identity remains unknown, according to Boyd.

“They were highly skilled problem solvers with a sophisticated cosmology and a robust iconographic system to communicate that cosmology,” Boyd said.

Dating rock art comes with significant challenges. But for their study, the authors used two independent radiocarbon methods that had typically not been used together to date paintings at 12 mural sites within the Lower Pecos Canyonlands. This ensured that the researchers could be confident that their dating results were consistent, study co-author Karen Steelman, a chemist and science director at the Shumla Archaeological Research and Education Center in Texas, told Live Science.

The researchers also analyzed the iconography and compositional makeup of the murals at the sites, finding that, in many cases, the artists appeared to have adhered to a strict set of technical rules and established stylistic conventions, even though they were created over a 4,000-year-period. For example, the authors determined that the creators generally followed the same sequence when applying colored paints to the artworks — a practice passed down over multiple generations.

The consistency that these complex murals display over several millennia, despite major environmental and technological changes — for example in stone tools and fiber crafts — indicate the persistence of an enduring cosmovision that must have been hugely significant to the hunter-gatherers, according to Boyd. This sophisticated cosmovision encompasses creation stories, the concept of time being cyclical and complex calendrical systems, among other elements.

The researchers have identified elements of this belief system in later Mesoamerican civilizations, such as the Aztecs, as well as among modern Indigenous American communities, like the Huichol of Mexico, she said.

“These paintings may be the oldest surviving visual record of the same core cosmology that later shaped Mesoamerican civilizations and is manifested today throughout Indigenous America,” Boyd said in a statement.

“The murals are viewed by Indigenous people today as living, breathing, sentient ancestral deities who are still engaged in creation and the maintenance of the cosmos,” Boyd told Live Science.