QUICK FACTS

Milestone: Staircase to King Tut’s tomb uncovered

When: Nov. 4, 1922

Where: Valley of the Kings, Egypt

Who: An archaeological team led by Howard Carter

On a sunny morning, Egyptian workers were clearing the sands at the Valley of the Kings, when they uncovered the hint of stone steps about 13 feet (4 meters) below the tomb of Ramesses VI.

The excavation team, helmed by British archaeologist Howard Carter but composed almost exclusively of Egyptians, had been clearing away sand near huts in the Valley of the Kings. Some stories hold that a water boy, Hussein Abd el-Rassul, may have been the first to spot the staircase.

When they found the steps, the group knew they had uncovered something important. The team worked feverishly until they reached the 12th step, where they discovered a small doorway covered with plaster, Carter wrote in his diary. On the door, they could partly make out the seal of the Royal Necropolis, which depicted the god Anubis as a king standing over the vanquished bodies of nine foes.

“Here before us was sufficient evidence to show that it really was an entrance to a tomb, and by the seals, to all outward appearances that it was intact,” Carter wrote in his diary on Nov. 5.

As they explored further, the team found that the entryway had been filled with rubble — likely by priests intending to block the tomb, which was further evidence the tomb had not been looted.

For the next few weeks, the team excavated the steps and the doorway until they uncovered a seal bearing the cartouche — an oval filled with hieroglyphs depicting a ruler’s name — of King Tutankhamun on Nov. 24. But the team still wasn’t sure who was buried inside, because the rubble filling the entryway had a confusing mélange of pottery shards and broken boxes that bore signs of other ancient Egyptian monarchs, including Akhenaten, Tut’s father.

On Nov. 25, they opened the first door to the tomb. The next day, they found a second door and cut a tiny hole inside to see what lay beyond it. No Egyptian officials were permitted to view the tomb, but Carter had brought along Lord Carnarvon, who had financed the tomb excavation; Lady Evelyn Herbert, Carnarvon’s daughter; and Arthur Callender, an engineer with the dig. All waited anxiously to see what lay inside.

“It was sometime before one could see, the hot air escaping caused the candle to flicker, but as soon as one’s eyes became accustomed to the glimmer of light the interior of the chamber gradually loomed before one, with its strange and wonderful medley of extraordinary and beautiful objects heaped upon one another,” Carter wrote in his diary.

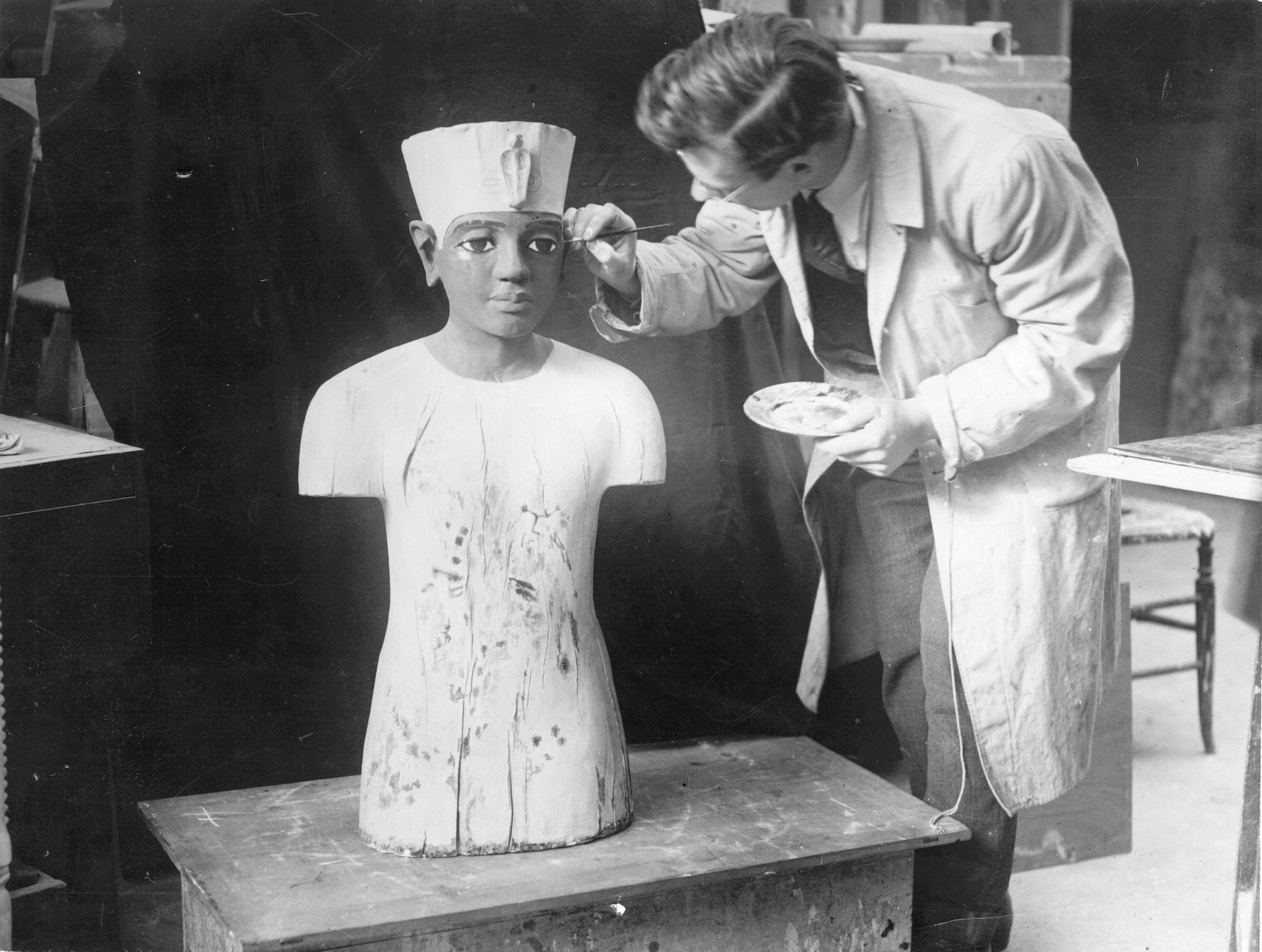

King Tut’s tomb was the first unlooted pharaoh’s tomb discovered in the modern era, and it was teeming with rich treasure. One of the most famous artifacts discovered was his ornate death mask, a 22-pound (10 kilograms) solid-gold face covering inlaid with semiprecious stones. But Tutankhamun was also buried with board games, several beds, and even a mannequin to try on outfits in the afterlife.

Tutankhamun was laid to rest in three nesting coffins — two made of gilded wood and the third (and smallest) of solid gold — and his body was soaked in oil that turned it black before he was mummified.

About a month after the tomb was opened, Lord Carnarvon died after a mosquito bite became infected following a shaving accident. And, in 1923, Pearson’s Magazine published a fictional story called “The Tomb of the Bird,” in which Carter’s canary was found dead in the mouth of a cobra soon after the tomb was opened. The rumor mill and media reports spun these and a handful of other flimsy coincidences into evidence of a mummy’s curse, the notion that whoever opened a pharaoh’s tomb would face an early or unnatural death. However, a 2002 study found that the 25 Westerners exposed to the tomb (and thus the “mummy’s curse”) lived about as long as would be expected for the time.