Neanderthals crafted red and yellow “crayons” tens of thousands of years ago, using different techniques to sharpen the instruments’ edges into a perfect point, a new study finds.

These Neanderthals, who lived in what is now Crimea, sculpted their crayons out of ocher (also spelled ochre), an iron-containing mineral that can be used as pigment. In the new study, the researchers identified three ocher crayons dating up to 100,000 years ago that appeared to have had “curated use,” including one with a sharpened tip.

The discovery of the crayon with evidence of repeated sharpening suggests that Neanderthals in Crimea sometimes used ocher for socially and culturally meaningful tasks, such as drawing body markings, according to research published Wednesday (Oct. 29) in the journal Science Advances.

Finding a fragment where the tip was clearly resharpened was exciting, said study first author Francesco d’Errico, a professor of archaeology at the University of Bergen in Norway, as it shows the crayon was crafted and maintained for drawing fine lines. “This is really something very special,” he said.

However, not everyone agrees with the researchers’ interpretations, telling Live Science that there is no direct evidence that these ocher crayons were used to draw cultural or social artwork.

This conclusion would hint at Neanderthals possessing the brain power to create social signifiers and to transform their bodies into cultural objects like our own species, Homo sapiens, does, d’Errico told Live Science.

Prehistoric pigments

Prehistoric humans and their relatives have been playing with pigments for hundreds of thousands of years. So far, almost 40 sites across Europe show evidence of Neanderthals using black, red, yellow or white pigments, but not all uses were for social or cultural purposes.

For example, Neanderthals living in Iberia around 50,000 years ago used red and yellow pigments to paint shells, suggesting symbolic use, while Neanderthals living in what is now the Netherlands were using black minerals 200,000 to 250,000 years ago without evidence of symbolic meaning.

However, there is less clear evidence of Neanderthals using ocher in Eastern Europe and western Asia, and the cultural variants found in those regions have received less attention, the authors wrote in the study.

To determine whether the previously unearthed ocher found at Crimean Neanderthal sites could have been used to create cultural meaning, the researchers focused on 16 ocher fragments from three Crimean rock shelters and one northeastern Ukrainian open air site dated from around 100,000 to 33,000 years ago.

The team closely inspected the ocher fragments’ shape and markings to see how they were crafted and used, and examined the elemental makeup of each fragment to determine where it originated.

D’Errico and his team found three fragments, all from Crimea, that they say were likely used for culturally meaningful purposes rather than simply for practical uses, such as tanning hides or repelling insects.

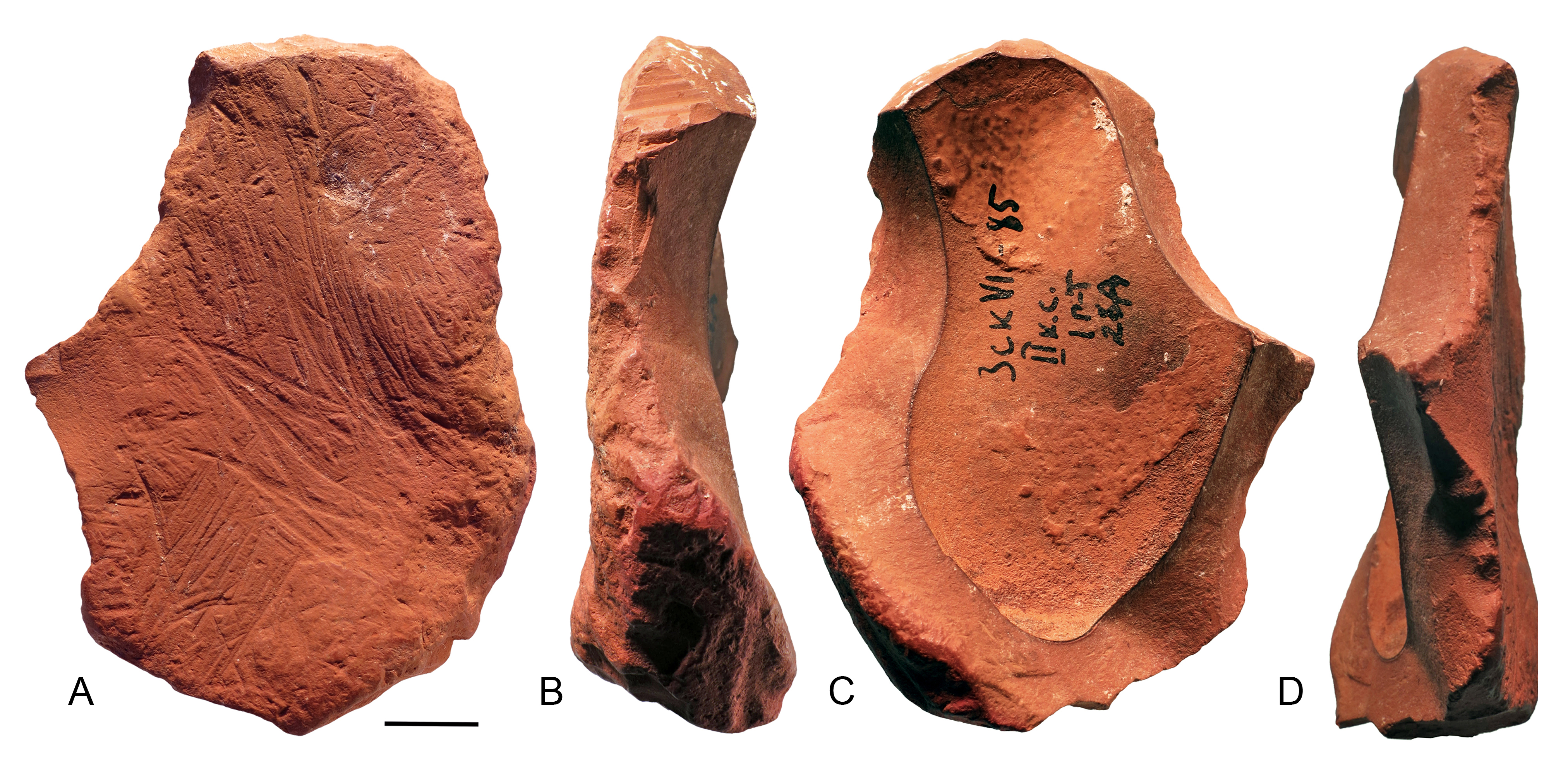

The first was a tool that had been repeatedly scraped and ground to sharpen its point after it became too blunt. This indicates that the ocher was used like a colored pencil to draw thin lines on surfaces such as skin or stones, the researchers suggested. Another fragment appeared to be part of a broken crayon, while a third piece had lines purposefully engraved into its base.

The ocher was sourced from the local outcrop, as well as other currently unknown locations, the team found. D’Errico said that tracing where Neanderthals obtained their coloring materials provides a window into the choices these individuals made and how they perceived differences in color and quality. However, the current sample of crayons is too small to reach any firm conclusions on these individuals’ decision making, he added.

A few disagreements

Rebecca Wragg Sykes, an archaeologist at the University of Cambridge and author of “Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art” (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) who was not involved in the study, is not convinced by the authors’ conclusions.

“The researchers’ argument that there is direct evidence for symbolic use here is not necessarily the only interpretation,” she told Live Science in an email.

For example, she said that the etchings on the side of one of the fragments do not necessarily mean it was culturally meaningful to the users. “The markings can be understood as a particular powder production method, without implying there was a particular symbolic meaning to them (e.g. as a recurring ‘motif’ or pattern),” she suggested.

But while the markings themselves may not have symbolic meaning, Neanderthals may have still used colored powders to that end, Wragg Sykes noted.

“The fact I do not think there is strong evidence here for intentional engraved motifs doesn’t mean that there was no aesthetic, socially meaningful element in why Neanderthals were making and using coloured powder,” she added.

April Nowell, a Paleolithic anthropologist at the University of Victoria in British Columbia who was not involved in the research, argues that there should be less focus on the distinction between symbolic and practical ocher use. Once Neanderthals started to use ocher for practical purposes, such as insect repellent, they likely also developed it for body painting and clothing designs to differentiate individuals or groups, as in nonindustrialized societies today, she told Live Science in an email.