Researchers have narrowed down the exact route that the interstellar interloper 3I/ATLAS will take as it begins its one-way trip out of the solar system.

Thanks to data collected from the alien comet’s recent close flyby of Mars, scientists at the European Space Agency (ESA) have refined the comet’s trajectory by ten-fold. And this could better help researchers unravel its secrets in the coming months, experts say.

After passing its closest point to the sun on Oct. 29, 3I/ATLAS has recently reemerged from behind the sun’s far-side relative to Earth. The trip around the sun was an eventful one: with the comet experiencing an unexpected brightening event, a temporary color change and a brief vanishing of its tail.

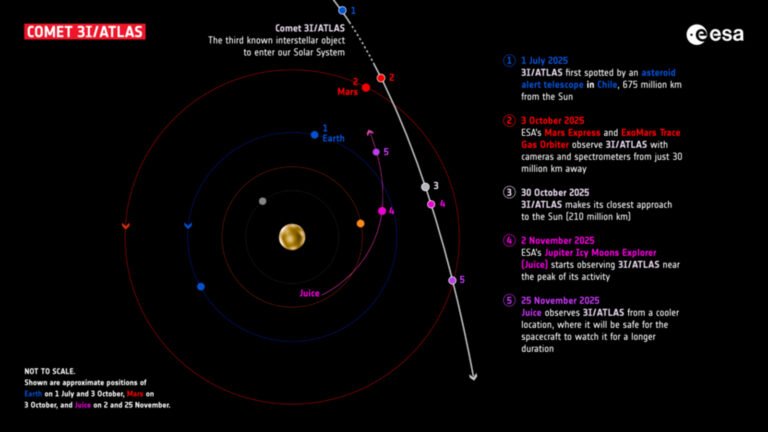

But before this, the comet also had a close encounter with Mars, coming within 18.6 million miles (30 million kilometers) of the Red Planet on Oct. 3.

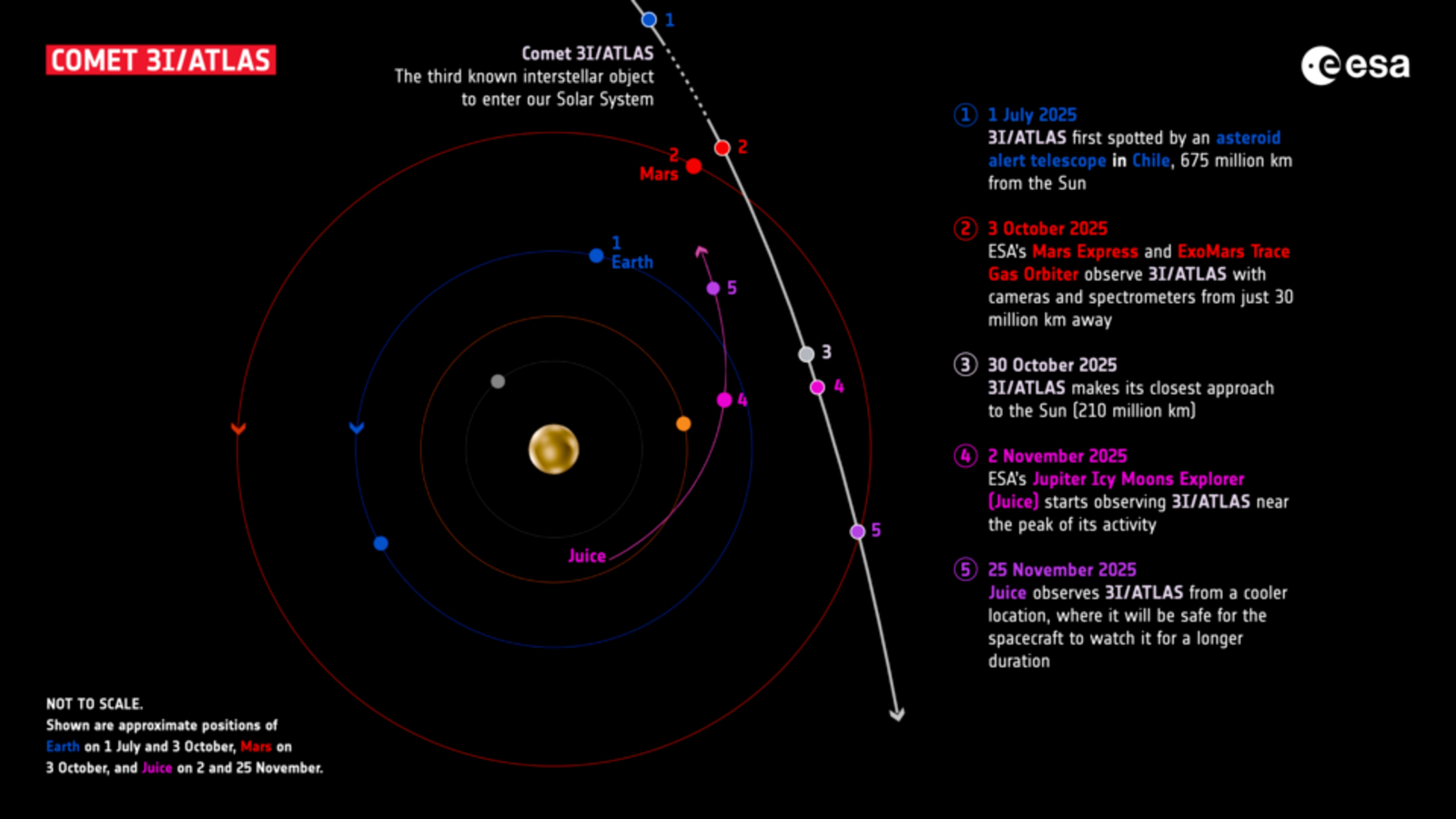

During the Mars flyby, the European Space Agency’s (ESA) ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter managed to snap highly detailed photos of 3I/ATLAS streaking toward the sun. By analyzing the orbiter’s data from this encounter, ESA scientists have improved predictions of 3I/ATLAS’s exit trajectory out of the solar system with a surprising level of success.

“While the scientists initially anticipated a modest improvement, the result was an impressive ten-fold leap in accuracy, reducing the uncertainty of the object’s location,” ESA representatives wrote in a statement. “The improved trajectory allows astronomers to aim their instruments with confidence, enabling more detailed science of the third interstellar object ever detected.”

Before now, researchers have been relying solely on ground-based observatories or Earth-orbiting spacecraft to track 3I/ATLAS’s position, which only provides specific views of the anomalous object. But by using observations from Mars, the ESA team could better “triangulate” the comet’s position, similar to how intelligence agencies track mobile phones using multiple cell towers.

However, factoring in the orbiter’s precise movements around Mars relative to the comet’s trajectory was no easy task. To make the process harder, the spacecraft’s Colour and Stereo Surface Imaging System (CaSSIS) is designed to photograph the Red Planet’s surface, not objects in space, the researchers wrote.

In fact, the method of imaging space objects with planetary orbiters is so hard that this is the first time that data from one of these spacecraft has been accepted into the International Astronomical Union’s Minor Planet Center database, which tracks the movements of all near-Earth objects, researchers wrote.

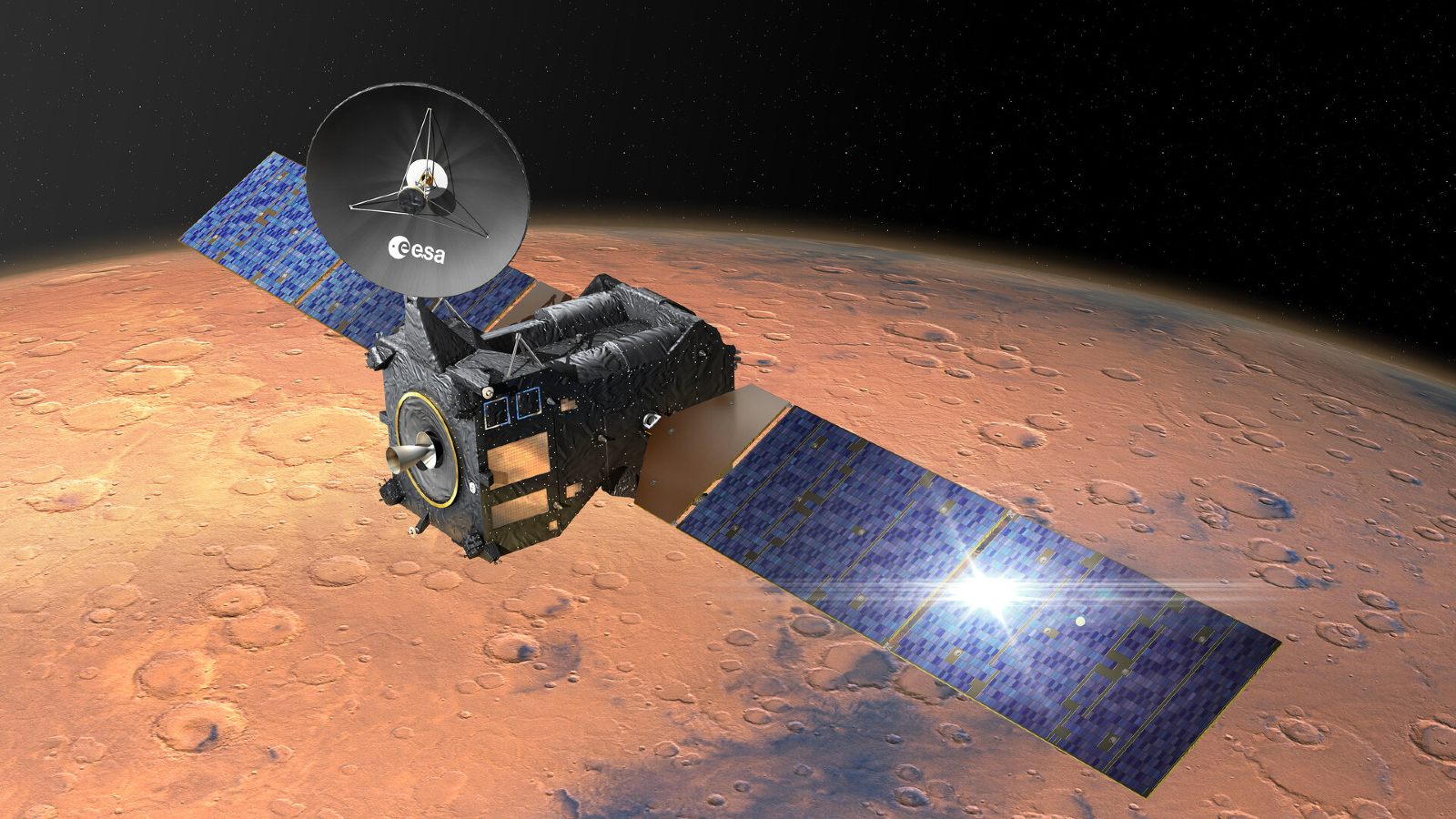

ESA is now hoping to repeat the trick with its Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE), which will get a good look at 3I/ATLAS later this month, researchers wrote. The agency’s researchers have also previously suggested that two of its other spacecraft, Hera and Europa Clipper, could also pass through the comet’s tail as it moves away from the sun.

During the recent Mars flyby, NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter also captured what could potentially be the best ever image of 3I/ATLAS, which some researchers predict could reveal more about its features. Due to the recent government shutdown, NASA has yet to release these images to the public. But recent reports suggest that these images could be released any day now.

3I/ATLAS will reach its closest point to Earth on Dec. 19, when it will reach a minimum distance of 168 million miles (270 million km) from our planet.