Forensic analysis of a 750-year-old skeleton has revealed that a Hungarian duke was brutally murdered by at least three assailants. Béla, Duke of Macsó, was stabbed more than two dozen times by weapons including a saber and a long sword, according to a new study.

“We reconstructed the order in which the blows landed by how they overlap and how a body would react, then what parts of the body would be exposed and suffer the next blows,” study co-author Martin Trautmann, an osteoarchaeologist at the University of Helsinki, told Live Science.

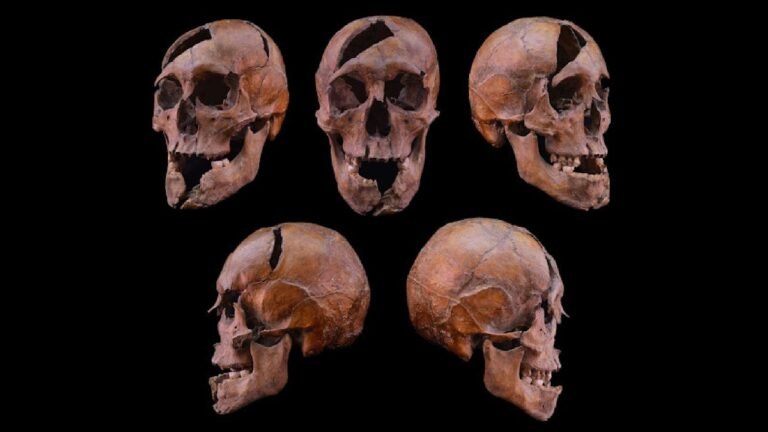

The team counted 26 injuries from about the time of death — nine to the skull and 17 to other bones. Their study is published in the February 2026 issue of the journal Forensic Science International: Genetics.

But the discovery of Béla’s cause of death is only one part of a twisty medieval murder mystery. During an archaeological excavation in 1915, the remains of a young man were discovered at a 13th-century Dominican monastery on Margaret Island, an island in the Danube River near Budapest.

Based on the location of the burial and signs of traumatic injuries on the bones, it was assumed that the remains belonged to Béla, a grandson of King Béla IV of Hungary who was born in about 1243, according to a historical record that mentioned the young man’s assassination in 1272. That account indicated that his mutilated remains were collected by his sister Margit and niece Erzsébet and buried in the monastery.

An initial investigation identified many sword cuts on the skeleton and injuries on the skull, but the bones went missing during World War II.

In 2018, the bones were rediscovered in a wooden box in the Hungarian Natural History Museum. But it was unclear if the remains really were those of Duke Béla, so study first author Tamás Hajdu, an archaeologist at Eötvös Loránd University in Hungary, and colleagues set out to investigate the mystery.

Skeleton study

Their analysis immediately hit a snag when radiocarbon dating produced a result that was before Béla was born.

“When we got the first radiocarbon results, we were shocked,” Hajdu told Live Science. But if Béla ate a lot of seafood, as royals of the time did, this could throw off the radiocarbon date, Hajdu said. This is because of the reservoir effect, in which aquatic animals consume or make shells from ancient carbon from the deep ocean or from old calcium carbonate, making their own carbon seem older than it really is. This old carbon then has a similar effect on the bones of whoever eats it.

A new analysis of microfossils found in calculus on the young man’s teeth indicated that he ate bread and cooked semolina flour, as well as a lot of animal protein, as might have been expected of a royal. He also ate a significant amount of aquatic animals like fish, they found.

Adjusting for the shift from this marine diet put the date into roughly the right period, Hajdu said.

Next, the team compared the skeleton’s DNA with DNA from two of Béla’s relatives: King Béla III (lived from 1148 to 1196) and Ladislaus I (lived from 1040 to 1095). This confirmed that the long-lost skeleton belonged to the grandson of King Béla IV, so the young man must be Béla, Duke of Macsó, the team reported.

Terrible injuries

A close study of Béla’s skeleton brought to light previously unknown details of his gory death.

Béla had defensive wounds on his arms and hands, Trautmann said, so he probably didn’t have a sword or shield available to parry the blows. The depth of the cuts on his remains also suggest he wasn’t wearing armor at the time, pointing to a coordinated, premeditated assassination that would have been very bloody.

“The attack very probably started from the front, and the first blows struck the head and the upper body,” Trautmann said. The cuts were made with at least two different weapons, an analysis found. “That tells us we have at least two different assailants,” Trautmann said — one from the front with the saber and one from the side with a long sword.

The duke likely reeled, was hit on the side, and fell down hard, smacking his head on the floor. “Probably, he was very dazed after this impact and tried to fend off further attacks with his arms and legs, which have defensive injuries from parrying blows,” Trautmann said.

One of the assailants stabbed the duke in the back, likely paralyzing him, Trautmann said, and Béla was finished off with more strikes to the head.

There were many more injuries than were necessary to kill him, which is known as overkill in a forensic context, Trautmann said, and it suggests an event full of hostile emotions.

One historical account had stated that Béla was killed by another noble, Henrik Kőszegi, and his allies. Béla and Kőszegi had been friends, and Kőszegi was originally Béla’s mentor, but that ended after a lost battle escalated matters, Trautmann said.

Rival factions of nobles were fighting for power at the time, and Béla, as someone with a claim on the throne, was likely seen as a threat who needed to be assassinated. “I think it was very personal,” Trautmann said.

Eleanor Graham, a forensic scientist at Northumbria University in Newcastle, England, who was not involved in the study, is convinced by the identification, even though the initial radiocarbon-dating results did not fit with Béla’s lifespan, she told Live Science by email.

“The claims made in the article are for the main part appropriately hedged and are supported by scientific evidence, including the forensic traumatological assessment which indicates an extremely violent death, and seems in keeping with historical accounts of the duke’s demise,” Graham said.