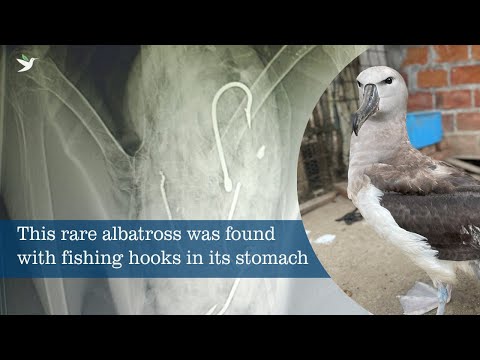

A rare seabird is recovering from a successful and life-saving surgery. A fisherman from Anconcito, Ecuador, found the juvenile Salvin’s albatross after he noticed that it appeared unwell. The bird had ingested four large fishing hooks and some fishing line and was brought to Puerto Lopez for rehabilitation and care. Local veterinarian Ruben Aleman removed the discarded fishing gear from the bird. After some extra R&R, the bird was released in late October on a nearby beach in Manabí province.

“Through coordination with Ecuador’s Ministry of the Environment’s local representative (REMACOPSE) and a specialized veterinarian, we successfully removed four fishing hooks from the bird, including one that caused injuries to its esophagus,” Giovanny Suárez Espín, Ecuador Seabird Bycatch Coordinator for American Bird Conservancy, said in a statement.

“The type and size of the hooks suggest they came from the artisanal mahi-mahi fishery, which poses a risk to albatrosses. While reducing bycatch in this type of fishery is challenging, we continue to promote best practices and more sustainable tools to minimize incidental seabird capture.”

The Salvin’s albatross (also called Salvin’s mollymawk) is a rare seabird species. It breeds in several rugged and remote subantarctic islands south of New Zealand. They spend the majority of their life at sea, foraging around Australia and New Zealand during their breeding period. After breeding, they fly thousands of miles nonstop to the Pacific coast off South America for food.

Since seabirds are so mobile and live in such a large area, protecting them takes a great deal of effort. Researchers in Ecuador and Peru and New Zealand’s Department of Conservation work closely with each other to study this species, advocating the fishing industry to do whatever it can to prevent seabirds from ingesting discarded fishing gear or getting tangled in nets and traps.

CREDIT: American Bird Conservancy

“While we collect tracking data from devices attached to adult Salvin’s Albatross, currently information on the movements of juveniles comes solely from observations,” added New Zealand Department of Conservation (DOC) Senior Science Advisor Dr. Johannes Fischer. “DOC plans to fit trackers onto juveniles at the end of this breeding season through a collaboration with Universidad Científica del Sur in Lima, Peru, which will directly inform seabird research partnerships in Peru, Ecuador, and other countries.”

Over the past 50 years, the Salvin’s albatross population has declined significantly. During the 1970s, there were roughly 88,000 breeding pairs, compared to about 50,000 today. These birds tend to begin breeding at 11 years old and only lay one egg per year. If the juveniles of the population are affected, there can be a long lag before negative impacts are seen.

While seabird populations have declined by more than 70 percent since 1950, they’re essential to the health of the entire ocean for one reason–their poop. Seabird droppings nourish the whole ocean and island ecosystems.

“These long-distance travelers depend on the productivity of the Humboldt Current to feed, yet each migration carries the silent risk of being hooked on longlines–a reminder that effective protection must transcend national boundaries,” said Dr. Carlos Zavalaga, Director of the Seabird Ecology and Conservation Research Unit from Universidad Cientifica del Sur, Lima, Peru.

Fishing vessels and equipment including gillnets, baited longlines, and trawls remain a major threat since they attract numerous foraging seabirds that are drawn to discarded fish and other food sources. In September, veterinarians in eastern Massachusetts successfully removed a large fishing hook from a black backed gull’s GI tract.

“Seabirds are one of the most threatened groups of birds globally, facing additional threats like overfishing, climate change, plastic pollution, and habitat loss. We all need to work together to protect these remarkable, wide-ranging animals,” Fischer said.

In Ecuador, the American Bird Conservancy’s Marine Program has been working alongside artisanal longline fisheries to reduce bycatch by developing new methods that are safer for seabirds.

“More than 2,000 fishers are helping us with bird conservation now,” said Espín. “The fishermen know that whenever they see a seabird species injured or one that has an issue, they have to let us know. And that’s what this fisherman colleague from Anconcito did.”